- Benchmark Education

- Newmark Learning

- Reycraft Books

- Create an Account

About the Experts

C.C. Bates, Ph. D.

C.C. Bates is an Associate Professor in Literacy Education at Clemson University in South Carolina, where she is the Director of the Reading Recovery and Early Literacy Center. C.C. has a Ph.D. from Georgia State University in Language and Literacy, and she is a former classroom teacher and reading interventionist. She is the author of Interactive Writing: Developing Readers Through Writing.

Patty McGee, M.Ed.

Patty McGee is an educator, author, and consultant. She has worked near and far—in her own hometown of Harrington Park and across the world in Abu Dhabi and many places in between. Patty’s passion and vision is to create learning environments where teachers and students discover their true potential and power through joyful inquiry, study, and collaboration. Her favorite moments are when groups of teachers are working with students together in the classroom. It is truly where the magic happens. Her latest book is Writer’s Workshop Made Simple: 7 Essentials for Every Classroom and Every Writer. Patty is also a contributing author to Benchmark Writer’s Workshop and the program author of Benchmark Grammar Study Mico-Workshop.

Related Resources

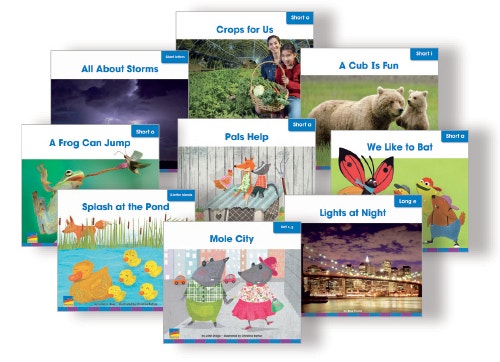

Decodable Readers

Print + Digital • English & Spanish • Grades K-1

Practice phonics and high-frequency words in context while nurturing a love for reading.

- Offers authentic practice with phonics skills and sight words through fiction and nonfiction titles

- Includes familiar storylines to ensure ease of reading and empower young readers to feel self-reliant

- Supports key literary, science, and social studies standards

- Increases engagement through high-interest topics

- Provides a variety of formats to fit any instructional model or budget

Episode Transcript

Announcer:

This podcast is produced by Benchmark Education.

Kevin Carlson:

What are we learning about how children learn to read? And how does that inform our instructional practices? In this episode, forget polarizing conversations around the science of reading. Instead, here's a focus on practical ways that theory meets practice in the literacy classroom. I'm Kevin Carlson, and this is Teachers Talk Shop.

Dr. C.C. Bates:

Instead of thinking about what side of the fence we are on, we need to kind of find the gate in the fence and we need to open that gate because there are things to be learned from both sides and there is definitely more common ground.

Kevin Carlson:

That is Dr. C.C. Bates, author of Interactive Writing Developing Readers through Writing. She is a professor of literacy education at Clemson University and the director of the Clemson University Reading Recovery in Early Literacy Training Center. Author and educator Patty McGee, talked with C.C. recently about using all we know about the sciences of reading to accelerate student learning. Here are Patty McGee and Dr. C.C. Bates.

Patty McGee:

I thought we could get together and have a conversation where we're bringing in the perspective of the sciences of reading and using all we know about the sciences of reading to accelerate student learning. So maybe we can begin just by talking about what we know is out there right now. There's a lot of tension that we've noted around reading instruction, and these tensions tend to make us pause and really affirm, rethink, revise our practices with students. And so I'm wondering if you could just maybe start us off with some of the things that you've been thinking about in terms of the tensions?

Dr. C.C. Bates:

Sure. I think that if we're not careful, this conversation around the teaching of reading becomes very polarizing. And, you know, people fall out on, I guess, on different sides of the fence. And I really wholeheartedly believe that everyone is here because they believe in empowering children to become literate. I think that instead of thinking about what side of the fence we're on, we need to kind of find the gate in the fence and we need to open that gate and we need to, you know, make sure that we are listening to the other side and that we are really thinking through what we know and what we're learning about how children learn to read and how that informs our instructional practices. Because there are things to be learned from both sides. And there is definitely, I think, more common ground. And when we get into these conversations, oftentimes on social media, you know, you see these kind of polarizing comments. I don't think that's in the best interest of children or teachers.

Patty McGee:

I hear you, and like you said, I think we have more in common. And I really think that common thread is that we all want to support students in becoming stronger and stronger readers.

Kevin Carlson:

After the break, making the theoretical practical. Stay with us.

Announcer:

In Interactive Writing: Developing Readers Through Writing, Dr. C.C. Bates explores what interactive writing is and how it connects oral language, writing and reading. When teachers understand those connections, they can help all students, including striving readers and English learners, advance and thrive as readers. In this professional development book, teachers will find tips on how to introduce, model, and practice interactive writing routines and save time by incorporating them throughout the school day. Tying science, math and social studies content in with reading and writing. The book also spotlights different types of formative assessments that help determine where students are in their learning and how to support their progress. Learn more at PDEssentials.com. Go teach brilliantly.

Patty McGee:

There's a lot of theoretical conversation that happens among grown ups and teaching reading, and that's really important. And what I think is equally or maybe even more important is now how do we take the theoretical and make it practical at the classroom level?

Dr. C.C. Bates:

I think, Patty, first of all, we have to know why we're doing what we're doing. So the rationale for the decisions that we make in a classroom is so important. And what feeds into that rationale is a deep knowledge and understanding about literacy and literacy processing. So I think sometimes where there is a disconnect is in the language that we use. So I may, in my work with children, refer to a letter combination or part, and I know how to speak to both audiences so I can clearly identify the difference between a phoneme and a grapheme. And I can use that language in conversations with colleagues at the university level. But that's not the language I'm using with children, and I think that's often the case with teachers. They understand what they're doing with children, but they may not use the language that represents that to researchers, to policymakers. And so oftentimes I think that there's this confusion around how teachers are coming to teach reading. And there's I think in some levels, maybe this goes back to the first question about these tensions in the field, a mistrust that teachers don't know what they're doing. And so we're going to simplify this and give them a prescription that every teacher is going to follow for every child. And what we know is that children are very individual in their learning trajectory. And so when we follow a lockstep prescription and we don't differentiate for children that are already know in control all of the skills that are set before me as a first grade teacher or children that still are working on recognizing the letters in their name.

Dr. C.C. Bates:

When I'm supposed to be teaching consonant digraphs, there's a disconnect there. And so as a teacher, I have to figure out how to differentiate my instruction to meet the needs of my learners. And I also, I think, really need to feel empowered as an educator that I know what I'm doing, that I have a strong rationale for the decisions that I'm making. And so I think part of that to elevate this conversation is to help teachers own that language around literacy teaching and learning, and to be able to clearly articulate that they do know the difference between phonological and phonemic awareness. So I think that at some levels, you know, we don't always give educators the credit that they deserve, that they are professionals and they know their jobs. So I think, you know, kind of unpacking some of that language being very clear, you know that we understand that a phoneme, you know, is that individual sound unit and that a graphene is the letter or letters that represent that sound. So, you know, I think sometimes when teachers are in pre service programs, we teach those things, but they get out in the field. And now all of a sudden they've got a child that's having difficulty. And so, you know, going back, I think in engaging in ongoing professional learning where we revisit some of these concepts that we're taught in a pre service program now in light of individuals in their current context.

Dr. C.C. Bates:

So what does that mean for me as a second grade teacher with a child or children in my second grade class that are reading well below grade level? So, you know, understanding that language in light of our current context and revisiting how that changes from child to child and grade level to grade level, I think those are important things that we need to understand. You know, there's a lot of conversation right now about phonemic awareness and about phonics. And I think really being clear about the definitions in terms that we're using so that we are all speaking the same language so that if I'm in a conversation with school administrators and teachers that and parents that everyone is on the same page. And when we talk about, you know, children having challenges around some of these issues that we are using a common language. So there's no concern that, well, the teacher doesn't really understand. And it may be because she's referring to some of the things that she's doing in the classroom and the ways in which she would talk to the children about those things. And you know, when I'm talking with children, I use terminology that's very different than I'm going to use with educators, and that's even different than oftentimes the ways in which I engage parents in conversation around the teaching of reading because there's a different level of understanding for all of those players.

Patty McGee:

Yes, absolutely. And I think that's so wise to say because if we can't speak a common language around supporting children and knowing that that language is going to shift with different people, depending on who we're talking to, but knowing that language across, like you said with children, with parents, with colleagues, with in professional settings, when we speak that common language, we are better able to communicate, especially around what you said earlier about where we have more common ground than we don't. So what comes to mind then after thinking about this common language, what comes to mind for me as an educator then is how do teachers go about finding those places and spaces within student learning to be able to figure out where instruction is most needed and what instruction is most needed? So of course, I'm coming then to assessment. So could you give us I know this is like a full college course, but if you could give us just some important things that as educators to either validate or remind us of assessing the whole student reader, of course, keeping sciences of reading in mind. But as we think about this practical part of looking at the whole reader, can you just give us a couple of things to think about?

Dr. C.C. Bates:

Sure. And I, you know, I say this pretty regularly, I think sometimes assessment is almost a dirty word. You know, it comes with so much baggage, but it really is what drives our instructional decision making. So I think sometimes it gets tangled up with standardized assessments and summative assessments where we're only looking at what they what children can do at the end of the school year. But really, as a teacher, what I need to know is how I'm going to get them from point A to point B. So it's really using assessments to determine where students are. And as an educator, it's incumbent upon me as a professional to understand that developmental continuum and the educational expectations for the grade level that I'm teaching. And then I'm going to use that information in tandem to really kind of chart a path for a child's accelerated progress. I have to know what this child knows and controls. And I have to see how that fits within the overall understanding of what a first grader is supposed to know and understand. In my particular district, in my particular state. So that also means how the standards, my state standards, you know, play into those educational expectations. And then it's really easy to see how each child's path is going to be different. So, you know, I mentioned just a couple of seconds ago about having children, you know at all different points in their literacy journey in a first, second grade, kindergarten classroom.

Dr. C.C. Bates:

I mean, we could name any point in a child's K-12 education and see how children are progressing at different rates, how they have different strengths and they bring to bear different things on their learning. And so as a teacher, if I don't know clearly that this particular child that I'm working with is a confusion between, let's say, H and N and R because those letters are all so visually similar and that child's still trying to sort that out. And I'm teaching for that. But my prescription that is mandated at the district level or at the school level tells me that I'm supposed to be working on consonant digraphs and I'm teaching SH. well, I've got a really now think about, that scope and sequence continues to march on. It doesn't matter that this child is still trying to sort out the difference between H and N and R and how they, you know, looks very, very similar. And so I've got to make sure that as this marches on, I'm still teaching this particular child. And so I think that's where we have to really think about, you know, children holistically and that I'm not teaching a class of 25. I'm teaching 25 individuals that each have very unique strengths and are on different paths on that continuum.

Kevin Carlson:

After the break, CC Bates gets practical about grouping. Stay with us.

Announcer:

With so many Decodable Readers available, how can teachers know which ones will best meet the needs of their young students? The latest science of reading research identifies three key factors that a decodable text must have to support effective reading instruction. They should be instructive, engaging and comprehensible. And these three characteristics are present in all Benchmark Educations decodable readers. Author and phonics expert Wiley Blevins: "For students, these stories and informational texts give them lots of opportunities to practice, extend and refine their knowledge of sound spelling relationships so they can get to mastery faster." To learn more about Wiley Blevins and Benchmark Education's Decodable Readers visit us at Benchmark Education.com.

Patty McGee:

You notice that students are having difficulty with this particular area, say the difference between R, N and H as letters. But the curriculum is saying that we should be teaching this, like you said, digraphs. How then does a teacher make a decision instructionally about that? Like, what are some things that we can as educators practically do when we have both the curriculum and also the information in front of us? What are some ideas you have for us?

Dr. C.C. Bates:

I think first of all, we have to be very careful about the way in which we engage in grouping practices, right? So if I'm expected to teach whole group all day long, I'm going to have a very difficult time differentiating my instruction to meet the needs of those individual students in my classroom. So I'm really looking to use that assessment to inform the ways in which I group children so I may need to work with a child one on one. I may need to pull a small group. I need to recognize that just because I pull a small group of children doesn't mean that those children should be slated in that small group all year long. So there should be an ebb and flow in our grouping practices based on the patterns that we're seeing from the data that we're collecting and how we are using those formative assessments to better understand our students and their needs. So I definitely think that it's around our grouping practices, it relates to differentiated instruction. And it's also in those moments when I am teaching whole group knowing how I can then tailor and adjust instruction to meet the needs of individuals in the moment. So, you know, that's a lot. I think we have to be very systematic in our assessments. We have to be very organized in the way we keep up with those assessments, and it also involves a level of reflective practice on my part as a teacher. So if I don't sit down at certain points, you know, in the day when that's possible and at the end of the day and reflect on what's happened.

Dr. C.C. Bates:

I'm not going to remember, you know, by the next the next day, I mean, really by probably later that afternoon. That gets lost in a sea of all of the other interactions that take place within a primary grades classroom or any classroom, for that matter. So I think being, again detailed in the ways in which we record the observations that we're making and then using those observations, not just getting them down, you know, on some kind of sticky note that's going to then transfer into perhaps a checklist on certain skills that I'm looking to see children control, but that I actually engage in that reflective practice, as I mentioned, so I can then use that information moving forward. I mean, it's really a multifaceted process. I can't do any one part and expect to meet the needs of children. All of those pieces, not only the observation, but the ways in which I record my observations, the ways in which I go through and then look for patterns and trends across what children are taking on so that during that whole group lesson, I know which children I can then for example, during interactive writing, call up to a chart to add to what we're getting down on paper, because for that particular child, there's going to be a connection there. It's right at their you know, critical point of something that they're taking on in thier learning, does that make sense?

Patty McGee:

It does. It does. And I'm just I'm just thinking about that and putting kind of what you said into some practical steps that almost summarizing what you're saying here. C.C. So what I think you're saying and tell me if this is correct is first, we know it's important for us as educators to know what we're assessing and whatever lingo we're using with different people, we all know what we're assessing and we're assessing that whole child. And as we are assessing that whole child more in a formative type of way rather than in a summative way, we're looking all the time at what students know, almost know and not yet know or, as you say control, maybe almost control or not yet control. And then we're making instructional choices based on that, and those instructional choices can be in grouping. It can also be in the content that we choose and also in the practices, just like interactive writing is one of those practices. So I think, did I miss a step in there?

Dr. C.C. Bates:

No, I think that's a great summary. And I'll tell you the end goal. I mean, is everyone has to know, right, SH for example. So it's not that I don't expect the child who's still sorting out the difference between these visually similar letters, not to get there. But if I don't deal with the confusions first, I'm never going to get them to recognize, you know, this letter combination that produces the sound. So it's really important for me to know and to dig down, because if I just expect the child to take this on and I think, well they're not learning it, but I don't drill down, I may not recognize that this is where the confusion lies. Right? So I've got to sort this out before I can move on to the, you know, to the grade level expectation of whatever it is. Does that make sense?

Patty McGee:

It totally makes sense. And I guess some of like almost layman's words that are coming to mind is that teachers are detectives first that we're like seeking out what it is that is the confusion. We're finding that and we know what our our destination is, but we're looking for the places that are challenging, that are challenging.

Dr. C.C. Bates:

Yes. And you know, I mean, I go back to the the title of one of Marie Clay's books that she wrote By Different Paths to a Common Outcome, right? And that is we all have the same end goal, but the ways in which children get there are going to be vastly different. And it's not just because one child may have some, you know, confusion around a few letters. It's also because children bring, each child brings a unique perspective to their journey as a literacy learner, and that includes, you know, their culture and, you know, their motivation to engage with text. And they are so much that feeds into that. So that piece too is so important that we understand our children and those funds of knowledge that they bring to the school setting and that we recognize those and value those and honor those is part of what takes them on that unique path to that common outcome.

Patty McGee:

Yes, absolutely. And you know what? I think those are beautiful words to end on. That really we're working with children, we're teaching children, we're educators of children, and we're looking at the whole child, not just their cognitive skills, but also who they are as humans, what they bring with them, their experiences, their motivations. It's a human experience teaching reading.

Kevin Carlson:

Thank you, Patty McGee. Thank you. Dr. C.C. Bates. And thank you for listening to Teachers Talk Shop. If you want to learn more about the science of reading, go to TeachersTalkShop.com and visit our archive. Episode 25 is called The Sciences of Reading and the Whole Child, featuring Peter Afflerbach and Rachael Gabriel. Episode 20, "Expanding the Science of Reading," features Peter Afflerbach. And Episode 4 features Wiley Blevins and is called The Science of Reading: What Brain Research Says About How We Learn to Read. While you're on the site, please register to receive updates about the show. For Benchmark Education, I'm Kevin Carlson.